Thursday, 28 February 2013

Wednesday, 27 February 2013

Tuesday, 26 February 2013

The 3x3 Magic Square, More Magical than You Thought!

I just came across an older article from the Journal of Recreational Mathematics about the 3x3 Magic square that reminded me of some beautiful relations in the square, and showed me a few I had never seen. The article is by Owen O'Shea and is titled "SOME WORDS ON THE LO SHU". If you want to search out the whole thing (well worth the read) it is in Volume 35(1) starting on page 23.

The Lo Shu Square ( literally: Luo (River) Book/Scroll) is the unique normal magic square of order three. Except for rotations or reflections it is the only order three magic square that can be formed with the digits 1-9. Chinese legends concerning the pre-historic Emperor Yu tell of the Lo Shu: In ancient China there was a huge deluge: the people offered sacrifices to the god of one of the flooding rivers, the Luo river, to try to calm his anger. A magical turtle emerged from the water with the curious and decidedly unnatural (for a turtle shell) Lo Shu pattern on its shell: circular dots giving unary (base 1) representations of the integers one through nine are arranged in a three-by-three grid. The representation in the more common Arabic Numerals looks like this:

The odd and even numbers alternate in the periphery of the Lo Shu pattern; the 4 even numbers are at the four corners, and the 5 odd numbers (outnumbering the even numbers by one) form a cross in the center of the square. The sums in each of the 3 rows, in each of the 3 columns, and in both diagonals, are all 15 (the number of days in each of the 24 cycles of the Chinese solar year.

Beyond the basics of the magic square, O'Shea points out several other interesting relations. First, the sum squares of the numbers in the top and bottom row are equal. 42 + 92 + 22 = 82 + 12 + 62 = 101. You can do the same thing with the two outside columns, 42 + 32 + 82 = 22 + 72 + 62 = 89. Go ahead, try the two diagonals, you now you are dying to know.

So what about the middle row and column? Well, the middle column is special; Because north is placed at the bottom of maps in China, the 3x3 magic square having number 1 at the bottom and 9 at the top is used in preference to the other rotations/reflections. As seen in the "Later Heaven" arrangement, 1 and 9 correspond with ☵ Kǎn 水 "Water" and ☲ Lí 火 "Fire" respectively. In the "Early Heaven" arrangement, they would correspond with ☷ Kūn 地 "Earth" and ☰ Qián 天 "Heaven" respectively. The 951 does have a nice numerical representation in the number. If you read the rows or columns as three digit numbers, you might notice that 492 – 357 + 816 = 951 and that 294 – 753 + 618 = 159. Kind of a transition from Heaven to Earth and back again.

An original O'Shea contribution is his discovery that, "Ignoring the middle column, form two-digit numbers with the other columns as follows: 42 + 37 + 86. These numbers sum to 165. Their sum of their

reversals, 68 + 73 + 24, is also 165. The same is true of 84 + 19 + 62 and their reversals, 26 + 91 + 48. Curiously, the sum of the squares of the odd digits, 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9, also equals 165."

If we go back to considering the rows as a three digit number, the square of each row numeral is the same as the square of their reversal: 4922 + 3572 + 8162 = 6182 + 7532 + 2942. Of course that would be really impressive if it worked with the columns too... I mean, awesome impressive... ahh go on, try it.

The article goes on with several dozen interesting numerical relations, and if that's your thing, you should seek it out. I'll leave you with one last beauty:

There is a not too well know problem in math called the Tarry-Escott problem which asks if there are sets of integers with the same order (same number in each set) so that the integers in each set have the same sum, the same sum of squares, etc.up to and including the same sum of kth powers.

Remarkably, the pattern in the lo shu gives a solution to the Tarry-Escott problem. Starting at the top left and reading around the outside you get the four three digit numbers, 492 ,276 , 618 , 834 . Now read them going the other way round, 438, 816, 672, 294. Now add up the numbers in each set. Add up their squares..... their cubes?

Historically, The magic squares appeared first in China. In 500

BCE, and 300 BCE, the river map is mentioned, but no explicit magic

square is given. In 80 AD Ta Tai Li Chi gives the first clear reference to a

magic square. In 570 AD Shuzun gives an actual description of a magic

square of 3. Not until 1275 do we hear of the Chinese making squares of

order larger than 3. *Mark Swaney

India seems to have developed magic squares, favoring 4x4 squares, as early as the first century AD. Larger 5x5 and 6x6 first appeared in Islamic works in the 10th century.

Fran Swetz in his Legacy of the Lo Shu, mentions Tibet and Japan in a section on "Who else Knew Aboutn Magic Squares. And in the section on "Who didn't Know About Magic Squares" he lists Babylonia, Egypt and Greece.

Magic squares came first to Western Europe around the niddle of the 15th Century. Luca Paccioli, in particular had a collection of magic squares and expanded on the work of Ahmid al-Buni of Algeria, who wrote many mystical writings in the 12th and 13th Centuries. He was also a talented mathematician.

Monday, 25 February 2013

Sunday, 24 February 2013

A Devilish Prime, The Devil is in the Details

The number itself is interesting in that it is one of a sequence of primes. It seems that 16661 is prime also, and 1xxx666xxx1 is prime if the xxx is replaced by an appropriate number of zeros. Harvey Dubner determined that the first 7 numbers of this type have subscripts 0, 13, 42, 506, 608, 2472, and 2623 [see J. Rec. Math, 26(4)].

16661 is an interesting prime itself it is one of a special case of primes for which the sum of its decimal digits is the same as the sum of its prime index. 16661 is such a number, since it is the 1928th prime, and 1 + 6 + 6 + 6 + 1 = 1 + 9 + 2 + 8 = 20

Dubner is himself a little known (certainly relative to his merits) individual. A a semi-retired engineer living in New Jersey, he is noted for his contributions to finding large prime numbers. In 1984, he and his son Robert collaborated in developing the 'Dubner cruncher', a board which used a commercial finite impulse response filter chip to speed up dramatically the multiplication of medium-sized multi-precision numbers, to levels competitive with supercomputers of the time, though nowadays his focus has changed to efficient implementation of FFT-based algorithms on personal computers.

He has found many large prime numbers of special forms: repunits, prime Fibonacci and Lucas numbers, twin primes, Sophie Germain primes, and primes in arithmetic progression. In 1993 he was responsible for more than half the known primes of more than two thousand digits.

In addition, he is credited with the invention of the first blackjack point count (The High Low Count) which is used by most blackjack card counters today.

I haven't yet been able to find a copy of the journal above, so I don't know if he was the first to find Belphagor's prime, or if he just extended a known streak.

So some questions come to mind: who first found that the number was prime, who/what was Belphagor, who named the Prime Belphagor and when, What's up with the upside down π symbol, and what is Voynich's Manuscript and what does it have to do with Primes or Belphagor or Pi?

Some of these questions still remain unanswered, so consider this as much a request for information as a presentation of such.

Belphegor, it seems, was/is a minion of the Devil. Wiki says he "is a demon, and one of the seven princes of Hell, who helps people make discoveries. He seduces people by suggesting to them ingenious inventions that will make them rich. According to some 16th-century demonologists, his power is stronger in April. Bishop and witch-hunter Peter Binsfeld believed that Belphegor tempts by means of laziness. Also, according to Peter Binsfeld's Binsfeld's Classification of Demons, Belphegor is the chief demon of the deadly sin known as Sloth in Christian tradition." So how did I guy as lazy as I am not know about this guy??? Just to lazy to look him up I guess.

Ok, so next I tried to track down the mysterious upside down π glyph that was used as the numbers symbol. It appears, the post says, in the Voynich Manuscript. This turns out to be an intriguing mystery of its own.

Wikipedia again, tells me that it is called "the world's most mysterious manuscript".

,is a work which dates to the early 15th century (1404–1438), possibly from northern Italy. It is named after the book dealer Wilfrid Voynich, who purchased it in 1912. Some pages are missing, but the current version comprises about 240 vellum pages, most with illustrations. Much of the manuscript resembles herbal manuscripts of the 1500s, seeming to present illustrations and information about plants and their possible uses for medical purposes. However, most of the plants do not match known species, and the manuscript's script and language remain unknown and unreadable. Possibly some form of encrypted ciphertext, the Voynich manuscript has been studied by many professional and amateur cryptographers, including American and British codebreakers from both World War I and World War II. As yet, it has defied all decipherment attempts, becoming a famous case of historical cryptology. The mystery surrounding it has excited the popular imagination, making the manuscript a subject of both fanciful theories and novels. None of the many speculative solutions proposed over the last hundred years has yet been independently verified.Wow, cool, but with seemingly nothing to do with primes, demons, or math other than the cryptographic problem ??? At least we have a background date. Whoever and whenever the symbol was attached to the prime, it was after 1912 when the Voynich document was purchased.

In fact there seem to be no occurrences of "Belphegor's prime" in a Google Book search, and none of the hits on a general web search dated before 2012, so it may well be that the name and use of the symbol are creations of someone, perhaps Clifford Pickover, that has occurred very recently.

So I ended up with more questions than answers, much like my ill-fated search for Gauss' pipe. But I did come across with a page with several interesting relationships involving the infamous 666 by a gentleman named Mike Keith. I have included a few I found interesting below. If these fail to satisfy, he has a plethora of other "Beastly" offerings here. :

666 is equal to the sum of its digits plus the sum of the cubes of its digits:

666 = 6 + 6 + 6 + 6³ + 6³ + 6³.

There are only 6 positive integers with this property.

The sum of the squares of the first 7 primes is 666:

666 = 2² + 3² + 5² + 7² + 11² + 13² + 17²

The triplet (216, 630, 666) is a Pythagorean triplet. This fact can be rewritten in the following nice form:

(6·6·6)² + (666 - 6·6)² = 666²

A well-known remarkably good approximation to pi is 355/113 = 3.1415929... If one part of this fraction is reversed and added to the other part, we get

553 + 113 = 666.

[from Martin Gardner's "Dr. Matrix" columns] The Dewey Decimal System classification number for "Numerology" is 133.335. If you reverse this and add, you get

133.335 + 533.331 = 666.666

And long after I first was inspired to write all this by a post from Clifford Pickover, I saw another reference to 666 in one of his tweets: "666 hides among 0s in Pi! The string 006660000 occurs in Pi at position 58,488,501 counting from the first digit after the decimal point."

A short time after I wrote this blog, I got a nice note from David Brooks with some information about this number that I was unaware of (0k, no surprise, lots of stuff I haven't figured out) which I share below:

"Some trivia about this prime that you may (or may not) be interested in. First, it is a "naughty prime" - it is composed mostly of "naughts" or zeros. Second, it is a "Repulican prime" - the right half (ignoring the middle digit) is a prime number, but the left half is not prime."

The OEIS sequences for both numbers are here :

Naughty Primes: http://oeis.org/A164968 10007, 10009, 40009, 70001....

And Republican Primes: http://oeis.org/A125524/internal 13,17,43,47,67,83,97,103,107,...

and for political equity, I should point out that there are Democratic primes as well, defined as you would expect from the definition of Republican primes above, http://oeis.org/A125523/internal

Saturday, 23 February 2013

Friday, 22 February 2013

Inspiration, Mathematical Beauty

Just came across this neat video from a 3-D computer graphic artist Cristóbal Vila. How many of these mathematical/inspirational objects can you name?

The video is also on his webpage (link below).

He also has individual objects from the video with explanations of their mathematical links.

Show it to your students, give them the links to the page, let them run with it.

Thursday, 21 February 2013

Wednesday, 20 February 2013

Why M for Slope

A new post of this is available at

https://pballew.blogspot.com/2019/11/why-m-for-slope.html

Abstract:

Over the many years I taught I developed a keen interest in the origin and use of the symbols and terminology of math. When the internet came around I jumped in pretty early with a web page on Mathwords, contributing on the Dr Math and Teacher to Teacher support Math Forum, and for several years, this blog. Over that time there are few questions that come up more often than the reason for the letter m as the symbol for slope in the standard American (and it does seem to be mostly American) linear slope intercept equation form, y = mx + b.

Almost no one seems to ask about the b, which is even more curious to me.

Tuesday, 19 February 2013

Monday, 18 February 2013

Sunday, 17 February 2013

Saturday, 16 February 2013

Casting out nines, or almost any other number

The utility of the process was that if you add, subtract or multiply two numbers, the sum or product produced will have the same digit root as the sum or product of the digital roots of the numbers in the problem. If you multiply 23 (with digital root 5) times 47 (with digital root 2), you would get a number that has a digital root of 1. The name casting out nines probably comes from the fact that you can simplify the work by simply crossing out any nines, or even pairs of numbers that sum to nine. In the image at top they show that 17,999 has a digital root of 8, which is much easier to see if you just cross out the three nines in the first place. In much the same way you can quicken the 42,572 by crossing out the 7 and 2 (one nine) and also the 4 and 5 (another nine) and only a single 2 is left.

I have played around with other divisibility rules, and even made up some of my own. If you want to read these early blogs first, you might try this one, or another here.

The reason I am reminded of all this is that I just read an interesting article by the almost unknown English mathematician, Henry Wilbraham (July 25, 1825 – February 13, 1883), in an old Cambridge and Dublin Mathematical Journal. He points out that you can construct a similar division technique for any number. The idea is to use the period of the smaller numbers repeating fraction to break apart the second number. As an example, if you wanted to test to see if some large number was divisible by 37, you would first find the digital period length of the decimal 1/37. It turns out that 1/37 = 0.02702702702702703 so its period is three.

Now we take the really big number we want to test, say 7,424,883,933,621. We want to know if that number is evenly divisible by 37, and if it isn't, what the remainder will be.

The variation in Wilbraham's approach, and as I point out later it's not really an a variation at all, is to break the larger number up into sections of three digits (the period of our divisor's reciprocal), so we would add the 621+933+883+424+7= 2868. Now just as we can continue to compute digital roots when casting out nines, because there are more than three digits here, we can recombine those to get 2+868 = 870. Now all we have to do is divide 37 into 870 and if it goes evenly, it's a factor of the larger 13 digit number. If not, the remainder we get will be the same as the remainder when dividing the original number.

Turns out 37 is not a factor of 870 but leaves a remainder of 19. The good news is that we know that when we divide 7,424,883,933,621 by 37, we will get the same remainder.

It turns out that the reason this works is the same as the reason that casting out nines works. The period of 1/9 is one,.11111....., so we add every digit.

The math behind this is simple enough that I think any bright high school kid could understand it. If the period of a numbers reciprocal 1/n is some number p, then it must be true that 10p-1 is divisible by n. In my example, 103-1 must be divisible by 37, and is.

So if we break our larger number, N, up into periods of p, and express the sets of digits as individual numbers, A,B,C,D... so that N= A+10pB + 102p...etc.

So we know that N= A+ (kn+1)B+ (kn+1)2 C.... and if we distribute all these kn+1 terms all the kn powers can be collected (and are thus a multiple of our smaller divisor, n) and the rest will be A+B+C... which is the sum of the periods, and thus the remainder. If this number is longer than the period of 1/n, we can apply it again by using the same reasoning.

I should point out, because Wilbraham is so unknown, he did not spend his entire mathematical life doing arithmetic novelties. He is known for discovering and explaining the Gibbs phenomenon, the peculiar manner in which the Fourier series of a piecewise continuously differentiable periodic function behaves at a jump discontinuity, nearly fifty years before J. Willard Gibbs did. Gibbs and Maxime Bôcher, as well as nearly everyone else, were unaware of Wilbraham's work on the Gibbs phenomenon.

Friday, 15 February 2013

Thursday, 14 February 2013

Wednesday, 13 February 2013

Tuesday, 12 February 2013

Monday, 11 February 2013

Sunday, 10 February 2013

Saturday, 9 February 2013

Tally Sticks and Keeping Score, a Brief History

Whenever you can, count.

~Sir Francis GaltonThe traditional tally stick has a very long history. I have written about it before, but wanted to add some notes to make a somewhat more comprehensive inclusion of some other types of tally marks that have been (and some still are) in common use.

The term "tally" comes from the name of a stick or tablet on which counts were made to keep a count or a score. The Latin root is talea and is closely related to the origin of tailor, "one who cuts". Many math words have origins that reflect back to the earliest and most primitive uses of number. Compare the origins of compute, digit, and score.

Beads and knots on chord have also been used for tallys. I am still looking for details on their use and will amend as I find more details. *Wik

|

| *Wik |

Around 1960 an ancient mathematical record on bone was uncovered in the African area of Ishango, near Lake Edward. While it was at first considered an ancient (9000 BC) tally stick, many now think it represents the oldest table of prime numbers.

The first record existing of tally marks is on a leg bone of a baboon dating prior to 30,000 BC. The bone has 29 clear notches in a row. It was discovered in a cave in Southern Africa. It is sometimes called the Lebombo Bone after the Lebombo mountains in which it was found. The exact age of such artifacts is a subject of debate, and their mathematical usage is somewhat speculative. Some sources have stated that the bone is a lunar phase counter, and by implication that African women were the first mathematicians since keeping track of menstrual cycles requires a lunar calendar.

Another candidate for the oldest tally record in history is a wolf bone found in Czechoslovakia with 57 deep notches cut into it, some of which appear to be grouped into sets of five.

The split tally was a technique which became common in medieval Europe, which was constantly short of money (coins) and predominantly illiterate, in order to record bilateral exchange and debts. A stick (squared hazelwood sticks were most common) was marked with a system of notches and then split lengthwise. This way the two halves both record the same notches and each party to the transaction received one half of the marked stick as proof. Later this technique was refined in various ways and became virtually tamper proof. One of the refinements was to make the two halves of the stick of different lengths. The longer part was called stock and was given to the party which had advanced money (or other items) to the receiver. The shorter portion of the stick was called foil and was given to the party which had received the funds or goods. Using this technique each of the parties had an identifiable record of the transaction. The natural irregularities in the surfaces of the tallies where they were split would mean that only the original two halves would fit back together perfectly, and so would verify that they were matching halves of the same transaction. *Wik

|

| *Wik |

In Mathematics Galore by Budd and Sangwin, there is a story of much more recent tally sticks. It seems that until around 1828 the British kept tax and other records on wooden tally sticks. When the system was discontinued they were left with a huge residue of wooden tally sticks, so in 1834 they decided to have a bonfire to get rid of them. The bonfire was such a success that it burned the parliment buildings to the ground. What Guy Fawkes could not do with dynamite the Exchequer did with tally sticks.... The power of math.

The story, as improbable as it seems, is varified by a speech by Charled Dickens 1855. [Charles Dickens, Speech to the Administrative Reform Association, June 27, 1855, in Speeches of Charles Dickens, ed. K.F. Fielding, Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1960, p. 206, ] The somewhat clipped version below is taken from Number, The Language of Science by Tobias Dantzig (pgs 23&24)

Ages ago a savage mode of keeping accounts on notched sticks was introduced into the Court of Exchequer and the accounts were kept much as Robinson Crusoe kept his calendar on the desert island. A multitude of accountants, bookkeepers, and actuaries were born and died... Still official routine inclined to those notched sticks as if they were pillars of the Constitution, and still the Exchequer accounts continued to be kept on certain splints of elm-wood called tallies. In the reign of George III an inquiry was made by some revolutionary spirit whether, pens, ink and paper, slates and pencils being in existence, this obstinate adherence to an obsolute custom ought to be continued, ..... All the red tape in the country grew redder at the bare mention of this bold and original conception, and it took until 1826 to get these sticks abolished. In 1834 it was found that there was a considerable accumulation of them; and the question then arose, what was to be done with such worn-out, worm-eaten, rotten old bits of wood? The sticks were housed in Westminster, and it would naturally occur ot any intelligent person that nothing could be easier than to allow them to be carried away for firewood by the miserable people who lived in that neighborhood. However, they never had been useful, and official routine required that they should never be, and so the order went out that they were to be privately and confidentially burned. It came to pass that they were burned in a stove in the House of Lords. The stove, over-gorged with these preposterous sticks, set fire to the paneling; the paneling set fire to the House of Commons; the two houses were reduced to ashes; architects were called in to build others; and we are now in the second million of the cost therof.

Several images of the fire was painted by J.M.W. Turner who watched the fire from a boat on the Thames. I have a clip that I can not credit that says, "The fire of 1834 burned down most of the Palace of Westminster. The only part still remaining from 1097 is Westminster Hall. The buildings replacing the destroyed elements include Big Ben's tower (oooh, side bar... Big Ben is not the name of the tower at Westminster, it is the name of the great Bell in the Chimes there.. admit it, you did NOT know that, well at least I didn't till recently), with it's four 23 feet clock faces, built in a rich late gothic style that now form the Houses of Commons and the House of Lords. These magnificent buildings are still the subject of many paintings, including my own Parliament, with the grand Westminster Abbey on their north." The one below hangs in the in a gallery in Cleveland, Ohio.

|

| *Wik |

Many cultures use number symbols that reflect this tally counting approach for the lowest numbers. Japanese, for example, uses horizontal bars to represent the first three numerals.

The idea of creating tally sticks to record agreed amounts may be suggested by the Chinese character for contract, which shows the character for knife with the character for stick. (or so I am told by those who are better at reading Kanji than I)

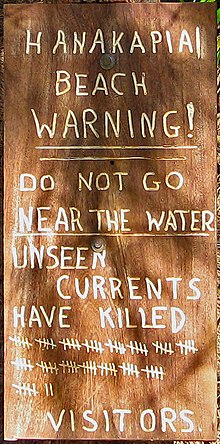

The problem with the traditional tally mark, is that larger numbers start to become difficult to count. For example, try to quickly determine the number of casualties indicated by this sign I found at Wikipedia:

At some point methods were developed to counter this. Our word score for twenty (you know, four score and twenty years ago..) is believed to come from making a more distinct cross cut to ease the counting of large groups. The use of a slanted fifth mark across the first four in sets of five is also now common for these types of tallys. Today our most popular pastimes remind us of our mathematical beginnings as they report the sports "scores", the number of marks for each team.

James A Landau noticed something of a puzzle about the use of score. He writes, "I checked the Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd Edition and found that the first citation for "threescore" was in 1388, for "fourscore" was in 1250, and for "sixscore" was in 1300. There were no entries for twoscore, fivescore, sevenscore, eightscore, or ninescore, which is a little curious. Why would people only start counting by scores at 60 and quit after 120?"

There used to be a unit called a shock for groups of 3 score. The following quote comes from a post by John Conway. "Most of the major European languages had a break after 60, which usually had a special name of its own ; for example, it was a "shock" in English before it became "three score". In Elizabethan times, the standard names for 60,70,80,90 were "threescore", "threescore and ten", "fourscore" and "fourscore and ten" and the other European languages did much the same thing. The word shock as an amount persisted in American use (albeit in a slightly changed form) at least until 1919 when James Whitcomb Riley's poem, "When the Frost is on the Punkin" was published. The first line reads, "WHEN the frost is on the punkin and the fodder's in the shock," but by this time it seems that the bundles of corn stalks, bundled and dried to use for feed, or fodder, may not have reflected a count of sixty as much as however many could be conveniently bound together.

Other methods of tallying have appeared in different places. I figure most are newer, but their histories seem very hard to trace (If you have information on early use of any of the following, I would love to hear of them.)

Wikipedia has several representations such as the one below they credit to French and Spanish cultures.

I have never seen this, and don't know if it is still in common use any.where. ("Anyone, Anyone.") I did imagine almost instantly that it could be assembled into sets of four to make a score, or any number near a score by progressing in some order towards something like this, which I imagine could quickly be seen as 18:

I vacillated between whether the four diagonals in a rhombus or an X array would be better, but avoided the X because of its association with ten in Roman numerals and such.

The successive strokes of the Chinese character for completion, or correct (it seems to have a variety of contextual applications)正 (

John D Cook had some notes that included the tally marks shown below, which he credited to the mathematician/statistician John Tukey. The method actually dates back to early use in the Forestry industry in the Americas as a method of keeping tallys. My earliest notation is from Forest mensuration By Carl Alwin Schenck, 1898 pg 47.

The final tally method I have seen comes from personal experience, and I can't find record of it anywhere. It was a method my parents used to use in score keeping in domino games. The method they, and most others play, scores points in multiples of five, so the only method needed was how many multiples of five had been scored. Their method shows the first five points as a larger diagonal, / and the next five produces a large cross, X. Afterwards they would proceed to fill in smaller slashes and x's in the four spaces around the first X. So that after 35 points (7 five point markers) the score would show something like this:

Since the game was played to 100 (or 20 five point scores) two of these completed would signal a win.

I have not seen this anywhere I have searched, but believe it must be pretty common, at least among domino players in the Southwest US. If you are familiar with this and can give dates of recorded usage prior to about 1950, I would love that information also.

In the meantime, I will keep searching and updating as I get new information.

As a footnote, Thony Christie wrote to tell me that " In German bars drinks are still tallied on the beer mats. " I take this to be from his direct experience.

Beads and knots as counters The earliest use of beads as counters may have been the development of prayer beads. Beads are among the earliest human ornaments and ostrich shell beads in Africa date to 10,000 BC. Over the centuries various cultures have made beads from a variety of materials from stone and shells to clay. How long they have been used to count prayers is unknown, but a Wikipedia site notes a statue of a holy Hindu man with beads dates to the 3rd century BC. The English word bead derives from the Old English noun bede which means a prayer.

Prayer beads is a little different, in my mind from typical tallys in that the object is not to record the number counted, but to count to a predetermined number without distracting the focus on the prayer or blessing. In some religions knotted ropes are used for the same purpose.

Beads on a string for calculating are described as early as the second century. These suanpan, or Chinese abacci are also not tallying devices in my mind, but more of a calculating device. However, others who have wasted part of their youth, as I did, in older pool halls know that they frequently had beads on a wire string above the table to mark off the number of points scored for each player in certain games. I saw a table top Foosball game with a similar device recently. But tallying with knots seems to have been in use in many cultures.

In the MAA Convergence online site, noted math historian Frank Swetz gives this description of the Inca use of knotted chords

Quipus were knotted tally cords used by the Inca Civilization of South America (1400-1560). The system consisted of a main cord from which a variable number of pendant cords were attached. Each pendant cord contained clusters of knots. These knots and their clusters conveyed numerical information. In some complex instances, further pendant cords were attached to these primary pendants. The number, type of knots, and knot and cluster spacing, as well as the pendant array, all conveyed particular information. A further dimension of this system was use of color: different pendants were dyed different colors, conveying different meanings. One of the few existing records of quipu use is found in the Chronicle of Good Government (1615/1616), written in Spanish by the Inca author Guaman Poma de Ayala.These quipas may have been more of a recording device than a counting device, but Professor Swetz's use of "tally" in his description make me think they may well have had tally purposes as well.

Also, in The Number Concept by Levi Leonard Conant he tells of "Mom Cely, a Southern negro of unknown age, finds herself in debt to the storekeeper; and, unwilling to believe that the amount is as great as he represents, she proceeds to investigate the matter in her own peculiar way. She had 'kept a tally of these purchases by means of a string, in which she tied commemorative knots.'"

I have also seen several books for children that suggest that "counting ropes" were employed in the Navaho culture in the United States, but have no idea how historical these stories are. So at least it seems that counting ropes were used in some cultures for counting.

I am still searching for more evidence of their use, and welcome comments.

Friday, 8 February 2013

Thursday, 7 February 2013

New Biggest Prime, but NOT Next Biggest

One of my ex-students, Savannah B., wrote to tell me she had read about the discovery of the newest "Largest Prime" recently, 257,885,161 − 1. This prime was discovered on January 25, 2013 by Curtis Cooper at the University of Central Missouri as part of the Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search or GIMPS. To perform its testing, the project relies on an algorithm developed by Édouard Lucas (You may remember that he was the guy who invented the famous Towers of Hanoi puzzle) and Derrick Henry Lehmer(the younger of the father/son team of number theorists and prime hunters). The algorithm is both specialized to testing Mersenne primes and particularly efficient working with binary computer architectures.

This particular prime is 17,425,170 digits long in it's decimal form. It would take 3,461 pages to display it. If one were to print it out using standard printer paper, single-sided, it would require approximately 7 reams of paper. (and no, children, I did not check that data)

The previous "Largest Prime" was around since 2009, and by comparison required a paltry 12,837,064 decimal digits to describe it. That number was 242643801-1.

When I responded to the note, I assured her that there were many more to be discovered; after all, the primes are infinite. But even more interestingly, that there are many primes guaranteed to be between these last two "Largest" primes. In fact I told her there were several million of them.

"But if they are not yet discovered, how can we know there are so many?" I hear you ask.

And I reply with one of my favorite rhymes from number theory"

Chebyshev said it, so I'll say it again,

there's always a prime between N and 2N.

This is sometimes called Bertrand's Conjecture, but Chebyshev proved it, so I prefer to give it the stature and deserved name of a theorem. Besides, I love to give his whole name. Pafnuty Lvovich Chebyshev. Now he was a pretty awesome mathematician with lots of notches in his proof belt, and due to the vageries of translating Russian into western tongues, you can find almost as many spellings of his last name, some starting with C, and others with T.

So what does that have to do with "several million" primes between 242643801-1 and 257,885,161-1

What Chebyshev has said is that if you have a number, say 30, then there will always be another prime between that number and 2x30, or 60. Sure enough there are several of them, 31 for example will work. You can try a few for yourself, but it will always work. That's why it's a proof.

Now if we look at any of the Primes of the form used in the GIMPS project, they all have an interesting similarity, they are one less than a power of two. Some very early Mersenne Primes would be 3=22-1, 7=23-1, and 31=25-1. What happened to the forth power? Well the definition only applies to prime exponents. In fact, some prime exponents don't work. 211-1 doesn't work. It's the product of 23 and 89. So what the GIMPS project does is use computers to check which ones work using the algorithm mentioned above. By the way, the Lucas guy in the algorithm name, He proved in 1876 that 2127-1 (which was on Mersenne's original list) is indeed prime, as Mersenne claimed. This was the largest known prime number for 75 years, and is still the largest ever calculated by hand. After that they started using calculation machines, then computers.

This Prime was the milestone for so long, that when BBC announced a new "baby" computer at Manchester University, they used proving it was prime as the ultimate test of the computer. In 1951 Ferrier used a mechanical desk calculator and techniques based on partial inverses of Fermat's little theorem to slightly better this record by finding a 44 digit prime: \(\frac{(2^{148} +1)}{17}\) = 20988936657440586486151264256610222593863921.

In that same year, the age of electronic computer records began when Miller and Wheeler found several new larger primes, including a 79 digit prime.

Another interesting thing about Mersenne Primes is that when you write them in binary, they use only 1's. Seven in binary, for example, is 111. And that new largest prime, in binary it is written with 57,885,161 consecutive 1's.

But for the beautiful theorem proven by my Russian buddy, Pafnuty, it is important to point out that each is more than twice the last. Let's start with powers of two. 2,4,8,16 etc. Chebyshev's theorem says that there has to be a prime in there between each pair. So when we get to 242643801-1, the second largest known prime, we know that 242643801+1-1 is one more than twice as much... and sing the jingle children... there must be a prime in there somewhere. between 242643801-1 and 242643802-2 in fact. And it turns out that between 242643801-1 and 257,885,161-1 we can expect to find another prime every time we step up a power of two. A total of 57,885,161-42,643,802= 15,241,359 primes at a minimum (and there could be many more).

The trouble is, in that first interval, between 242643801-1 and 242643802-1

there are 12,837,064 numbers to be tested(THIS IS OH SO WRONG, See correction below). Of course you can eliminate half of them as even right off the bat, and when you eliminate the multiples of three you will have narrowed the search down to only a third of that, or about 4 million numbers. So crank up the old PC and get crackin'. Would love for one of mine to discover the next "Second Largest Prime." Keep in mind, it would be the "Largest" non-Mersenne Prime ever found.

Fact checking correction: Joshua Zucker was kind enough to send a comment to correct my gross math error in that count of the numbers to be checked. As he pointed out, the number I gave was a gross underestimation of the number of digits to be checked in that first interval between 242643801-1 and 242643802-1. He points out that there must be N numbers between N and 2N, so we need to check 242643801-1 numbers. This number simply dwarfs the original number into obscurity.

But don't lose hope. Joshua also points out that there are also probably many more primes than the absolute minimum guaranteed by Pafnuty's gem of a theorem.

It is somewhat well known that a good approximation for the number of primes up to some n is given by \(\pi(n) \approx \frac{n}{\ln(n)} \). Actually this approximation tends to under-approximate the number of primes. It has been found to be improved by subtracting one from the denominator. For example the original approximation predicts 144 primes below 1000. Turns out there are actually 168. The adjusted value dividing by log(1000)-1 predicts 169... see, better. The good news is that both approximations are very good when the numbers get large, and 242643801-1 as I have pointed out above, is very large.

So here is the arithmetic as given by my Wolfram alpha app, 5.747041164664005282865876855507854781902617... × 10^12837055 is the number of primes expected up to 242643801-1. The number predicted using twice this amount is 1.149408205979101362235389622701947229078465... × 10^12837056. So the difference leaves almost as many between the two numbers as there are up to the first, or roughly 5.747 × 10^12837055. That is such a huge number, you would think they would be popping up everywhere, so like I said before,

It did get me wondering though. What is the largest number that we can say with confidence that there is no undiscovered prime less than that number. I'm sure we know all the primes up into some number of millions. Norman Lehrer, the father of the Lehrer in the theorem at top supposedly published tables of prime numbers and prime factorizations, reaching 10,017,000 by 1909. Surely that has been improved on. So, as the teacher in Ferris Bueller says, Anyone... Anyone?"

Wednesday, 6 February 2013

Tuesday, 5 February 2013

Monday, 4 February 2013

Mechanical Drawing with Harmony, a Brief History

Sometimes blogs start when some kind of reoccurring theme pops up over several days. In this case the theme was (loosely) drawing things using parametric functions. I saw the image above which is the Logo for the MIT Lincoln Library. It reminded me of something called Bowditch (or Lissajous) curves which were a common amusement I would use to introduce my students to parametric equations after graphing calculators. (more about these later) And I mused that someday I would have to look up the history of mechanical methods of producing parametric functions.

Then within a short period of time I read that André Cassagnes, the French inventor of the Etch A Sketch, had died near Paris on January 16, 2013, at the age of 86. If you haven't heard of the Etch A Sketch, (right) it was a mechanical toy that was used to draw on a screen with an internal stylus that was moved right or left by one twist knob, and up or down by the other, sort of a mechanical x=f(t) and y=f(t).

It reminded me of my earlier intention a few days earlier, and so I decided to begin filling out my knowledge about that history.

From my own notes I knew that Nathaniel Bowditch, an under-appreciated American self-taught mathematician had drawn curves like this. He first drew these parametric curves in 1815 with a compound pendulum."

Like most others, in school I had learned about them as Lissajous figures, images we drew on oscilloscopes using signal generators for the two inputs. But then,shortly after I first read about Bowditch I happened to be in Tokyo Visiting the Edo Museum for an exhibit named Worlds Revealed - The Dawn of Japanese and American Exchange. Like others, I had always had the misconception that Commodore Perry opened trade with Japan in 1853, so I was surprised to find that a number of American ships from Salem, Massachusetts, sailing under Dutch charters had traded with the Japanese as early as 1800. The company was called the East India Marine Society, and in 1802 the First Secretary was Bowditch. On exhibit was a much more popular mathematical creation of Bowditch; his book, The New American Practical Navigator, that Bowditch, and the Marine Society had published in 1802. The book was a compilation of the most accurate measures of the period giving the positions of major astronomical objects at numerous longitude and latitude coordinates. The book was, literally, a mariner's bible until an accurate sea clock would become commonly available that allowed sailors to conquer the longitude problem. Bowditch's position and accomplishments seem even greater in light of the fact that he was almost totally self educated in mathematics.

Then, in August of 2008 I read a post by Milo Gardner on the almost unheard of Wilkes Expedition, which explored the western Americas and the Pacific, and Milo added that "... mathematicians during the early 1800's were assigned to working on Manifest Destiny issues and projects. On the Wilkes Expedition you'll find Bowditch as one of its navigators. An island in the Pacific is named for Bowditch, since it had not been on any US or European map prior to the expedition's visit." The island, I found out, is sometimes called Fakaofu, and is located in the Stork Archipelago in the South Pacific.

I decided to go back a little farther by looking for any historical references I could find for the history of mechanical curve drawing and hit a jackpot with an on-line article by Daina Taimina, of Cornell University titled Historical Mechanisms for Drawing Curves. It seems to be from the book,Hands on History: A Resource for Teaching Mathematics.

She stated that "Mechanical devices in ancient Greece for constructing different curves were invented mainly to solve three famous problems: doubling the cube, squaring the circle and trisecting the angle."

She went on to give several examples, "There can be found references that Meneachmus (~380-~320 B.C.) had a mechanical device to construct conics which he used to solve problem of doubling the cube. One method to solve problems of trisecting an angle and squaring the circle was to use quadratrix of Hippias (~460-~400 B.C) {this was the first named curve other than circle and line – it is also the first example of a curve that is defined by means of motion and can not be constructed using only a straightedge and a compass.}

Proclus (418-485) also mentions some Isidorus from Miletus who had an instrument for drawing a parabola.[ Dyck,p.58]. We can not say that those mechanical devices consisted purely of linkages, but it is

important to understand that Greek geometers were looking for and finding solutions to geometrical problems by mechanical means. These solutions mostly were needed for practical purposes."

From her description it would seem that none of these still existed in physical or drawn form.

While her focus was on the use of linkages to create mechanical movement and drawings, I was searching for something closer to the idea of a parametric curve.

Certainly the early trammel which dates to Proclus or Archimedes (indeed it is sometimes called the trammel of Archimedes) but again, it is more of a mechanical linkage than parametric. And no offense intended to my neighbors here in Kentucky, but the instrument is often sold as a novelty made of wood with a crank knob on the end of the trammel bar that traces out the ellipse, and is referred to as a "Kentucky do-nothing".

Students may have also been shown how to draw an ellipse by taking a loop of string looped around two thumb tacks. By holding a pencil pulled against the string to keep it taut, and sliding it around the two thumb tacks as you keep the string taut, the pencil will trace out an ellipse. The first written description of this method of construction an ellipse by means with string was by Abud ben Muhamad, in the 9th century.

Then I came across an article in Wikipedia about the harmonograph, a mechanical platform that employs one or more pendulums to create a geometric image. Interestingly, they give credit for the first harmonograph to Scottish mathematician Hugh Blackburn. Trouble is, Blackburn was born in 1823; almost a full decade after Bowditch had written about his use of such a device.

I am beginning to accept that Bowditch may have been the first person to create the parametric images which sometimes, and should more often, bare his name. If someone has an example of an earlier non-linkage apparatus that suggests parametric input to draw figures, I would love to be notified.

Jules Antoine Lissajous, for whom the figures are more often called, invented a different type of device to create the images. He used a beam of light bounced off a mirror attached to a vibrating tuning fork, which then reflected off a second mirror attached to another vibrating tuning fork which was perpendicularly orientated (usually of a different pitch, creating a specific harmonic interval), which was then reflected onto a wall, tracing the figure.With frequency produced by audible frequencies the curve traced out by the light appeared as a complete image due to visual persistence. Lissajous device is sometimes credited with inspiring the two pendulum device, but he too was born after Bowditch had written of his device. None of this should be seen to diminish Lissajous mathematical stature. His experiments with waves, his novel method of creating the waves, and his dramatic lectures and demonstrations, including one at the Royal Society in London, exposed them to a much wider audience. These lectures were so impressive that he was awarded the Lacaze Prize in 1873 for his optical observation of vibration and, in particular, "for his beautiful experiments". Almost certainly he was completely unaware of Bowditch's work.

When I introduced these to my students I often used one similar to the Lincoln Library Logo at top and I called it the Chinese finger cuff curve (I am still waiting for the rest of the mathematical world to adopt this term, fall into line people) As I neared retirement it seemed that many of the students had never heard of finger cuffs, but there were always a few who knew of them, and often at least one student who would produce one from home over the next few days.

If you want to create you own, you can find on-line parametric graphers and even an ipad app for a harmonograph.

Several nice examples, with their equations, are given at this Wikipedia link. Enjoy

Sunday, 3 February 2013

Saturday, 2 February 2013

Friday, 1 February 2013

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)