Sometimes I enter the math contest they host at the Wild About Math blog site, and usually am among the people who get a correct answer, but haven't been the lucky name pulled from the hat yet. A recent problem about divisibility got me thinking about testing divisibility by seven again.

The problem was actually about divisibility by eleven, and asked

Consider all of the 6-digit numbers that one can construct using each of the digits between 1 and 6 inclusively exactly one time each. 123456 is such a number as is 346125. 112345 is not such a number since 1 is repeated and 6 is not used.

So.... How many of these 6-digit numbers are divisible by 11?

The answer, of course, is none.

Of course, is a danger word, like obviously, or trivially, in which we dismiss the idea that there is thinking involved. If I were presenting this question to a class, and I have, I would say it differently.

"None of these numbers are divisible by eleven, can you figure out why without test dividing any of them? "

If you don't see it, don't worry, I'll spill the beans on how I would prove it down the page. Just take a moment and try it yourself.

K

I

L

L

I

N

G

T

I

M

E

T

O

LET

YOU

THINK

The divisibility rule for eleven most commonly known is to take the digits abcdef and add every other one from the back, and then subtract the alternate ones. So f-e+d-c+b-a For example, 123456 would be 6-5+4-3+2-1=3. Now they can only be divisible by eleven if the result is 0, or a multiple of 11.

So if we think about the numbers involved in all these numbers, they all have three odd numbers, and three even, so no matter how you split them, you'll have one group is odd, the other is even, so the difference is an odd number. You can't get zero. But can we get eleven? Ummm, NO, because if we put all the big ones in one clump (6+5+4), and all the small ones in another (3+2+1), the difference is less than eleven.... so NONE of them are divisible by 11. There is another pretty easy test of divisibility by 11 that is similar to a general method usable by any prime. Unlike casting out nines, it doesn't give the exact remainder.

My interest was piqued by a response by Jonathan, of the jd2718 blog made these observations about the 6! or 720 possible numbers formed with the six digits as described:

As a consolation, all 720 of them are multiples of 3.

Half of them (360) are even (multiples of 2)

One in 6 (120) are multiples of 5.

Eight in thirty (192) are multiples of 4.

None are multiples of 9.

Fourteen of 120 (84) are multiples of 8.

Multiples of 7? New puzzle, good place to stop.

It is Not surprising that Jonathon covered all the other one digit divisors but did NOT test seven. Seven is the one that books on mental math simply say "divide by seven"; but thinking about it, it shouldn’t be too hard

I wrote recently about a mental test for divisibility by seven but it did have one flaw. It worked fine to tell you a number was divisible by seven, but if the number was not divisible by seven it did not give the correct modulus. Casting out nines will always give you the correct modulus. The sum of the digits of 2134 is 10 which has a digit root of 1, so if you divide 2134 by 9 you get a remainder of one. My rule for seven didn't give the true remainder.

The remainder when you divide a number by seven (or any other number) is frequently called the modulus. I've mentioned this before, it is just a way to divide integers into sets. Odd numbers are all equivalent to 1 mod 2 (they all leave a remainder of one when you divide by 2) and even numbers are all equivalent to zero. If a number is equivalent to zero mod (something) that means it is divisible by that (something). One of the things that makes them effective is the simple rule that if a+b=c then for any modular index n(the number you are dividing by) c mod n = a mod n + b mod n. For example 25 mod 7 = 4. We could have found that by breaking it into parts. Since 25 = 20 + 5 we find 20 mod 7 = 6, and 5 mod 7 = 5... and the 6+5 = 11 which is equivalent to 4 mod 7. So now we have the basics.

Every increase of one in the units increases the modulus 1, and every increase in the tens increases the modulus three, (for example 21 mod 7 = 0; 31 mod 7 = 3,and 41 mod 7 = 6). I figured out that the rest would be an increase of two in the hundreds, six in the thousands (think minus one) four in the ten-thousands (minus three?) and five in the hundred-thousands (minus two….) so the sequence applied to our test number, 546231… and what a coincidence, if you multiply 5(-2)+4(-3)+6(-1)+2(2) +3(3) + 1(1) …YOU GET -14, which is zero mod 7, the sequence of modulii used in each place makes it a multiple of seven…(546231 = 0 [mod 7]…

but wait, if you used the A-2B method in the blog above, we would notice that 231 by itself is a multiple of seven, since 23 - 2(1) =21… and 546 is also. [54 - 2(6)=42].. You could also apply that approach step by step, 54623-2*1=54621; and 5462-2(1) = 5460. The zero we can throw away because 546 tens is not divisible by 7 if 546 is not, so we proceed to 54-2(6) = 42 and hey, we have a divisor by 7. In each case we just combined two moduli to reduce the size of the number.

Note: the A - 2B method briefly says take call the last digit B, and the previous digit string A, then if 10 A + b is divisible by seven, then A - 2B is divisible by 7. 224 is divisible by 7; in fact, it's 7 x 32. If we write it as 10x 22 + 4, then the method says 22 - 2x4 is divisible by 7 also. since 22 - 8 is 14. I'll come back to why it tests numbers not divisible by seven, but gives the wrong remainder sometimes later, but first.

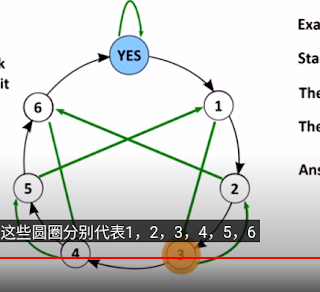

There is even a neat graphic approach that works very much the same way as the 2A - B approach, but proceeding from front to back, and it gives the correct remainder. I recently came across a nice video of that at a site by Presh Talwalker called Mind Your Decisions.

OK, so can we use the graph from the video to correct the remainder on the 2A-B method? And maybe a little explanation about Why it works. Most kids realze that on way to divide is to repeatedly subtract the divisor until you get a number too small to subtract again. 24 -7 = 17, 17-7 = 10 , 10 - 7 = 3 so 24 is three sevens and three more or 3 R 3.

But subtracting one at a time is pretty slow with big numbers, so we could subtract bunches of sevens all at once. We learned above that 224 was divisible by 7. So what if we subtracted ten sevens, 70, in a bunch, or we could subtract 140, or 210 (and this is a really good way to test divisibility by seven and it preserves the remainder. And that's how the A - 2B method works, with a gimmick. To keep the calculations simple, we use a rule that shortens thew length of the number on each operation. (Just as the video showed using one digit at a time).

If we are going to make the number shorter, we need to subtract something that will get rid of the last digit. It works because of a fact about multiples of seven you may never have noticed. For every ending digit, there is a multiple of 7 that has twice that digit in the ten's column; 21,, 42, 63, 84, 105, 126, ....

So when test 224, we begin by subtracting 84 to get 140. You know that 140 is only divisible by 7 if 14 is, so we can throw away the zero and continue with 14. For really really long numbers, not having to keep all thos zeros on the end reduces the writing, especially if you only care if it is divisible by 7 or not, and don't need the remainder because that gets messed up in the zeros...but it is recoverable using the graph on the video.

So let's walk through a slightly bigger number, doing it with and without dropping the zeros.

5162 sounds like a winner.

Longer ----------------------------------------A-2B

5162 - 42 ====> (5120) 516 - 4 = 512

5120 -420=====> (4700) 51 - 4 = 47

4700-14700 ===== (-10000) 4 - 14 = -10

Ok, -10, or 10 is not divisible by 7, and neither is -10000. Perhaps you could see the fact at 47 without going negative. Ok, two questions. What about that negative remainder. and is that the right remainder? If you not familiar with modulus, just add back sevens (or multiples there-of) and get a small positive. -10 + 14 =4, but wait, 47 - 42 = 5. It seems like the remainder is jumping around on us. Wait, remember the Green arrows used in the video for multiplying by ten? Well we are dividing by ten. To get our -10 or 4, we had divided three times.So lets ride the Green arrows, rebuilding from the bottom this time since we are anti-multiplying. Our final 4 remainder maps to a remainder for the previous 2 digit number, 47. The 5 maps to 1, and guess what the remainder of 512 divided by 7 is. Now we have to go back one more The 1 maps to 3, and that is the correct remainder....front to back, or back to front.

Another divisibility check is a little more work, but has a neat tie to vectors, so I'm adding it. check is make a function for the first n digit modulii you can just write them out multiplied times the correct modulus for that place value and probably check it in your head, but you would have to check each one… so making up a sequence, 234561(this covers everything up to six digits, but if you have a super memory, figure out another period), we would think 2×5=10 (the first digit times the first modulus) drops to 3, plus 3(second digit)x4(second modulus) is 15 which drops to modulus of one, now add 4(6) to get 25 and drop to mod 4, then add 2×5 to get 14, and we are at mod 0 [so 234500 is divisible by seven] and we know that 61 is NOT divisible by seven, so we can be assured that 234561 == 61 == 5 mod 7… ok, not EASY, but certainly could be done sans calculator…. [footnote, for those of you who have just gone through a pre-calc class and somewhere along the way they taught you about vectors, you probably imagined that you would never run across another dot product in your life, but you just did. IF you think of the sequence of modular values as one vector (5,4,6,2,3,1) and the six-digits of the number as a second vector, then the dot product is an integer that has the same modulus as the original six digit number....come on... that's pretty cool use of vectors!!!]

It is easy enough to write/remember the modulus up to ten-thousands (6231) to make this pretty useful as a factoring tool if you really needed the correct modulus. If the number is 4723 we just think 4(6)=24--==; 3 + 7x2---==; still 3, + 2(3)=9 --==;2 and then + 3(1)= 5 so 6231 divided by seven leaves a remainder of five.

Now 11 has a very similar method to the A - 2B method, But it's A- B. Is 43726 divisible by 11? 4372-6 = 4366, 436-6 = 430, and zeros are freebies , so we have 4-3 = 1. Nope not divisible by 7. In this case, the one is the true remainder, but not always. Consider 21, which obviously has a remainder of 10, but the A - B method gives 2-1 = 1.

If you continue methods for all the primes less than 20, they follow similar approaches. The approach for 19 would be A + 2B . An easy way to show it works is to apply it to any multiple of 19. If we use 95 = 5 x 19, 9 + 2 x 5 =19 (divisible by 19), 19 x 13 = 247, let's try it. 24 + 2 x 7 = 38, and 3 + 2 x 8 = 19.

Let's make up a longer number we won't know for sure 198273456. Step by step, 1982734 5 + 2 x 6 = 19827357; and 1982735 + 2 x 7 = 1982749; 198274 + 2 x 9 = 198292; 19829 + 2 x 2= 19833; 1983 + 2 x 3 = 1989; 198 + 2 x 9 = 216; and 21 + 2 x 6 = 12. Not divisible by 19.

A moment to clarify, What determines A + 2B from A - 2B or other to come. Suppose we have a number that is a multiple of seven and we break it up as 10 x 7k + 21 N. the last digit must be the same as N. try 10 x 2x7 + 21 x 3. that's 140 + 63 = 203. The 3 has to come from the multiples of 21, and since that last digit is 3, there must be three of them, or 13 or 33 or... but if we subtract 3 of them, we will still preserve divisibility by seven. The three ones came with six tens, so each time we cross off the ones, we are reducing the tens by twice as much. When we adjust 161 with 16-2 to get 14, it's a short cut for 161 - 21 = 140, but a number n times ten is only divisible by 7, if n is divisible by 7, because 10 isn't.

With 19, once more we are at almost two tens, so we use addition to make the ones go to zero. Think of 133 If we add 60 ( three twentys) to 133, we get 193, but now it is not divisible by 19, it has three extra in the units digit, so we get rid of the 3 by subtraction to get a multiple of 19, 190. And for our quick algorithm, we drop the last digit of zero because dividing by ten does not change divisibility by nineteen if the last digit was zero. Is 19 divisible by 19, then so is 133.

We do a similar thing with 13. 3 x 13 = 39, almost four tens. Our rule is A + 4B. We need to use the add on method like 19. Let's look at some multiples of 13. 13 becomes1 + 4 x 3 = 13; divisibility retained. 26 is transformed into 2 + 4x6 = 26, check. Maybe something bigger. 15 x 13 = 195. 195 morphs into 19 + 4 x 5 = 39 which is three thirteens.

For 17, we get close to a multiple of ten with 3 x 17 = 51, so we expect our divisibility to be preserved by an algorithm of A - 5B. Let's try a few. 17 becomes 1 - 5 x 7 = -34, which is divisible by 17.

17 x 346 = 363. Trying the rule on that we begin, 36 - 5 x 3 = 17, and success. 17 x 1345 = 22865. We begin with 2286 - 5x5 = 2261. Then 226 - 5 x 1 = 221. Finally 22- 5 x 1 = 17.

Once you see the method, you could create shortcuts for any prime. 3 x 23 = 69; nearly 7 tens. I would try A + 7 B. 29 seems quick, almost three tens. Try A + 3B. 1044 is 36 x 29. We use 104 + 3 x 4 = 116. Then 11 + 3 x 6 = 29....seems to work. -37. see

31 seems easy, but 37? What do you think, and remember, there can be more than one way for lots (all?) of these. Do you think A - 11B? Let's check, and if that works, think you are on your way. 37 x 17 = 629. We begin with 62 - 11 x 9= -37. Seems to work.

Have Fun!

No comments:

Post a Comment